Fritz Ascher and his Golem: Remembering Forgotten Artists

Published Oct 6, 2022

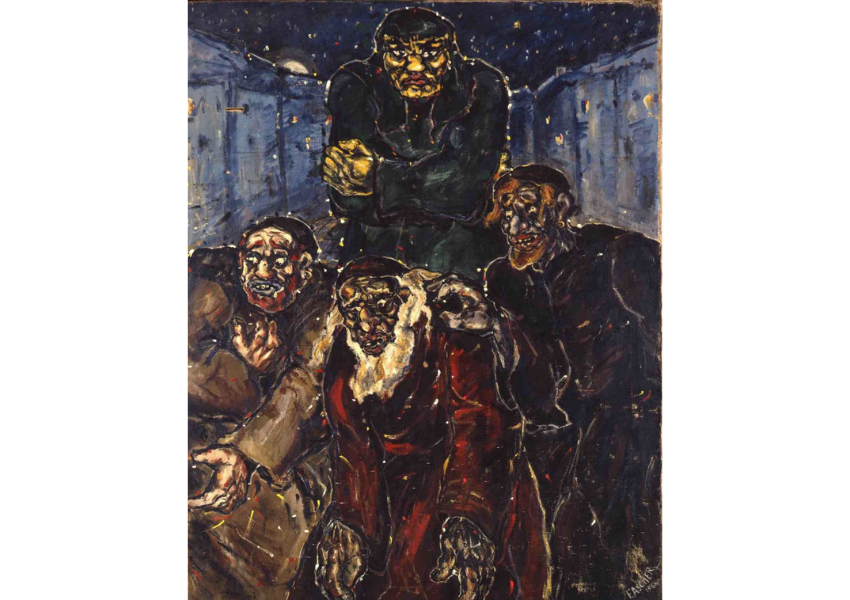

Fritz Ascher’s 1916 painting The Golem impels questions regarding art and identity.

Rabbi Judah Loew (1520/25-1609) created the Golem (meaning unformed in Psalm 139:16). Emulating the divine creation of Adam from earth (adamah), Rabbi Loew—with two assistants, one a Kohayn and the other a Levite—also shaped his Golem of earth. The process culminated by his placing the ineffable Divine Name (or the word, Truth) in the Golem’s mouth (or inscribing it on his brow) to animate him.

The Golem drew water from the river — a local messiah — to rescue endangered Jews. But one day when the Rabbi was away, an assistant activated the creature with no idea of how to stop it, and chaos and destruction ensued. Loew realized the dangers that accompanied the positive possibilities of his Golem and de-activated it: removing the Name of God/Truth from his mouth (or erasing it from its forehead).

Fritz Ascher (1893-1970) would have been familiar with this story through the novelized 1914 version by the non-Jewish writer, Gustav Meyrink Ascher, through work for the satirical Berlin-based magazine, Simplicissimus. Ascher grew up in a Europe where assimilated Jews struggled with acceptance/rejection and inclusion/exclusion within the larger (Christian) community. Indeed, a year after his birth, the Dreyfus Affair exploded. Ascher’s father, Hugo, and his children, (but not their mother), turned to the Protestant faith in 1901—probably for socio-economic reasons and concern for the children’s future. Young Fritz grew up between Jewish and Christian identities. Ascher’s Golem’s face offers ferocity and sadness; the other three figures—Rabbi Loew flanked by his assistants—have rather ghoulish expressions, notably limited teeth, and inordinately large hands. While the Golem looks out directly at us, they all look down and to the side, as if fearful of something (perhaps the vicious anti-Semitic Priest Thaddeus, in one version of the story)—or they are just unwilling to look us in the eye? Ascher has reversed expectation. His Golem looks less demonic—more human—than his human makers. Does this reflect a conscious or unconscious anti-Jewish bias? But Ascher’s benign Golem towers protectively (hence his ferocious expression) over the others, reflecting a Jewish understanding of the Golem as messianic. An ambiguous religious identity resonates from his canvas.

Ascher’s career crashed into the 1930s. Denounced by the Nazis as a Jew, forbidden to paint, arrested during Kristallnacht and brought to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, he was moved to Potsdam Prison and then freed six months later, through the efforts of a lawyer friend and an Evangelical Protestant minister. For two years he lived openly, but when the Berlin police officer to whom he reported weekly told him that he was scheduled for deportation, he went into hiding, surviving for three years in the basement of a partially bombed-out villa tended to by a friend of his mother. Limited to writing intense poetry, he returned to painting after war’s end—primarily expressionist landscapes—but that is another story.

Ori Z Soltes is the co-editor, with Rachel Stern, of The Expressionist Fritz Ascher: To Live is To Blaze with Passion. His essay in that volume on Ascher’s Golem offers extensive context for the work. See also: https://fritzaschersociety.org/

Photo: “Der Golem” (“The Golem”), 1916. Oil on canvas, 71 x 55 in. (182.5 x 140.5 cm). Signed and dated on lower right, “F Ascher 1916”. Verso signed, “F Ascher/Der Golem”. Jewish Museum Berlin GME 93/2. Photo Hermann Kiessling ©Bianca Stock

Ori Z. Soltes teaches at Georgetown University across a diverse range of disciplines.

Reflections

Unpacking Jew-ish-ness

What does it mean to be a Jew? How do ethnicity, religion or spirituality, culture, and conscious versus unconscious identity inform our definitions?

Unpacking “Jewish art”

What is Jewish art? Is it based on the subject or style or symbols within an artwork or the identity of the artist. Is this a matter of birth? Conviction? Conversion?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox